War on Normal People—Summary, Notes, + Quotes

Is universal basic income the answer?

Andrew Yang was a U.S. presidential candidate in the 2020 election who caught the attention of myself and millions of others through his unique approach to identifying and solving many of America’s problems.

These problems and solutions were published in his book The War on Normal People.

This book had a big impact on me. I have a better understanding of the kind of life the average American has and it increased the empathy I have for those in our country who are less fortunate than me. Yang brings up a variety of problems Americans face (and solutions), which I haven’t heard from politicians before. This had me questioning “what are the success metrics for a country?” And not least of all, it convinced me universal basic income should be seriously considered.

The book is divided into three parts: jobs, people, and solutions. The thesis of each are as follows.

Jobs

Millions of jobs have and will continue to be lost to automation and artificial intelligence. New jobs created from emerging technology won’t cover the amount of jobs lost, new jobs will be consolidated in cities abundant with tech and highly educated talent, and the people who do lose their jobs can’t be trained to fill the new jobs. This will cause a “great displacement” of tens of millions of workers across the country, affecting rural and small cities the hardest.

People

In the second part, Yang reveals more of his personal philosophy as he shows how the quality of American life is deteriorating. This quote sets the stage:

“…many of us came up through the meritocracy and we’ve internalized its lessons. The underlying logic of the meritocratic system is this: if you’re successful, it’s because you’re smart and hardworking, and thus virtuous. If you’re poor or unsuccessful, it’s because you’re lazy and/or stupid and of subpar character. The people at the top belong there and the people at the bottom only have themselves to blame.”

Andrew Yang

High rates of unemployment and under employment are linked to an array of social problems, including substance abuse, domestic violence, child abuse, drug abuse, depression, lower marriage rates, and the fragmentation of the family structure with rising rates of single mothers.

Solutions

In part three, Yang lays out his case for a new way forward, beginning with changing the utility of free market capitalism.

“We must make the market serve humanity rather than have humanity continue to serve the market. We must simultaneously become more dynamic and more empathetic as a society.”

Andrew Yang

With the rise of automation and artificial intelligence (AI), capital will continue to consolidate and leave people behind.

“In the United States, we want to believe that the market will resolve most situations. In this case, the market will not solve the problem - quite the opposite. The market is driven to reduce costs. It will look to find the the cheapest way to perform tasks… The market will continue to throw millions of people out of the labor force as automation and technology improve. In order for society to continue to function and thrive when tens of millions of Americans don’t have jobs, we will need to rethink the relationship between work and being able to pay for basic needs.”

Andrew Yang

His solution is a form of universal basic income (UBI) of $1,000/mo for every American citizen from the age of 18 to death. One thousand dollars is somewhat of a magic number. It’s not enough to live off and serve as a job replacement, but it’s enough to serve as an income supplement.

Summary of The War on Normal People

Yang’s thesis on the economy and the future is this: automation and AI is putting us through the “fourth industrial revolution.” This will cause millions of workers to be displaced, especially hitting rural communities the hardest. The solution is a universal basic income to help people through the transition, provide an influx of money into every community in the country, and give people a bigger safety net.

His universal basic income proposal would cost ~$3 trillion per year, while the existing federal budget is ~$4 trillion. Before looking more into his proposals to fund it, here is his reasoning for why it’s needed in the first place. Note that there are far more data points in the book than presented here. I simply chose what I think to be most interesting.

Part one: What’s happening to jobs

In this section, there are several chapters full of statistics to show how the current economy is not benefiting “normal people.”

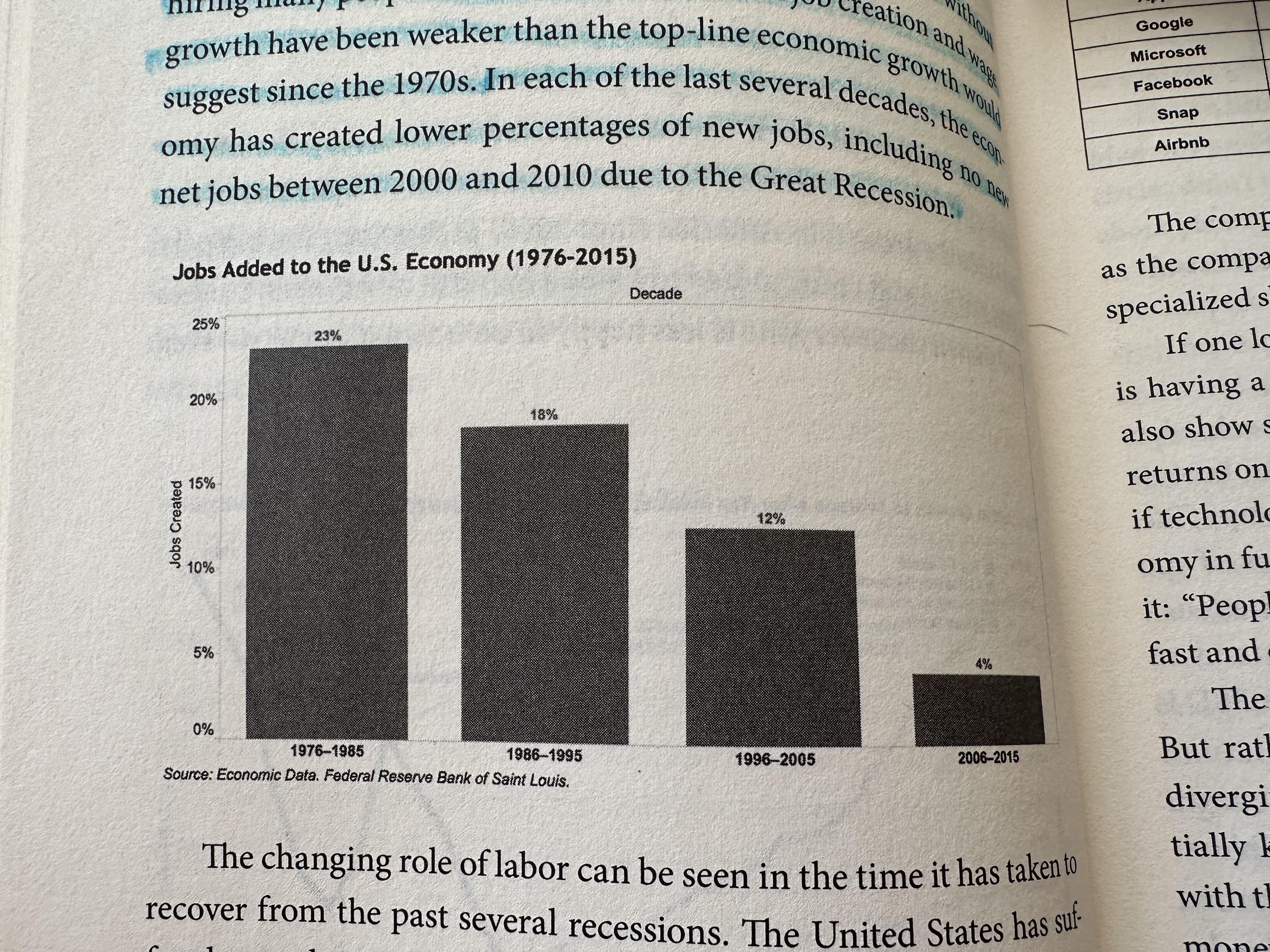

Job growth has been on the decline

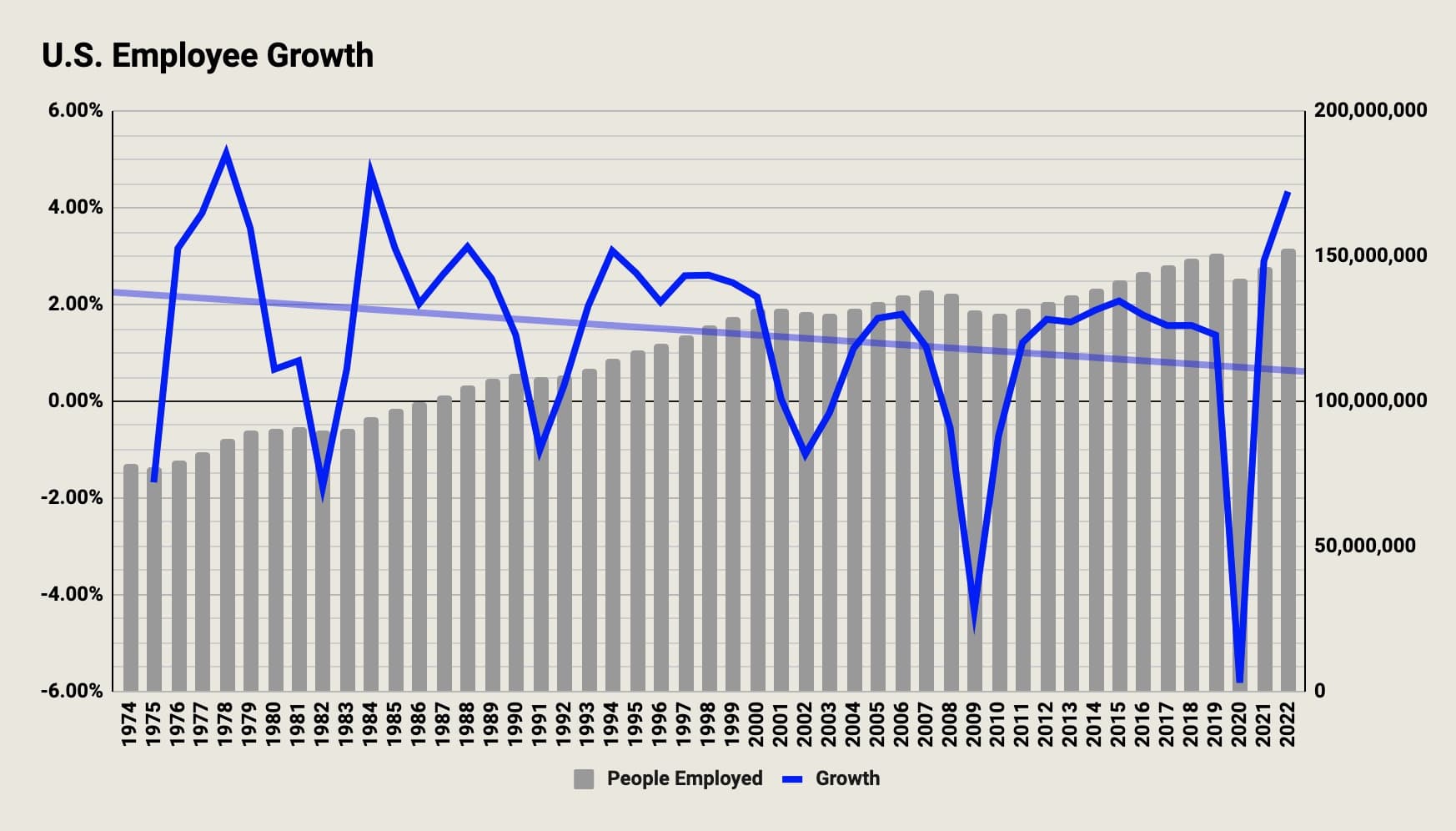

Through the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, we can see historical data for the total number of employed people over the past several decades. Although the number of employed people is clearly not decreasing, the rate at which it’s growing is on the decline.

In the book, Yang shows job growth is on the decline, but he presents it grouped by ten-year-long increments. When I downloaded this data and looked into it further, I found this narrative of declining job growth to change based on where you start the groupings. With Yang’s choice, job growth appears to be on a sharp decline.

But why not just present the annual growth rate in a line graph?

The periods of declining job growth align with economic recessions and, as Yang points out, each of these recessions have “stripped out more jobs and taken longer to recover from than the last,”. This does appear to be true.

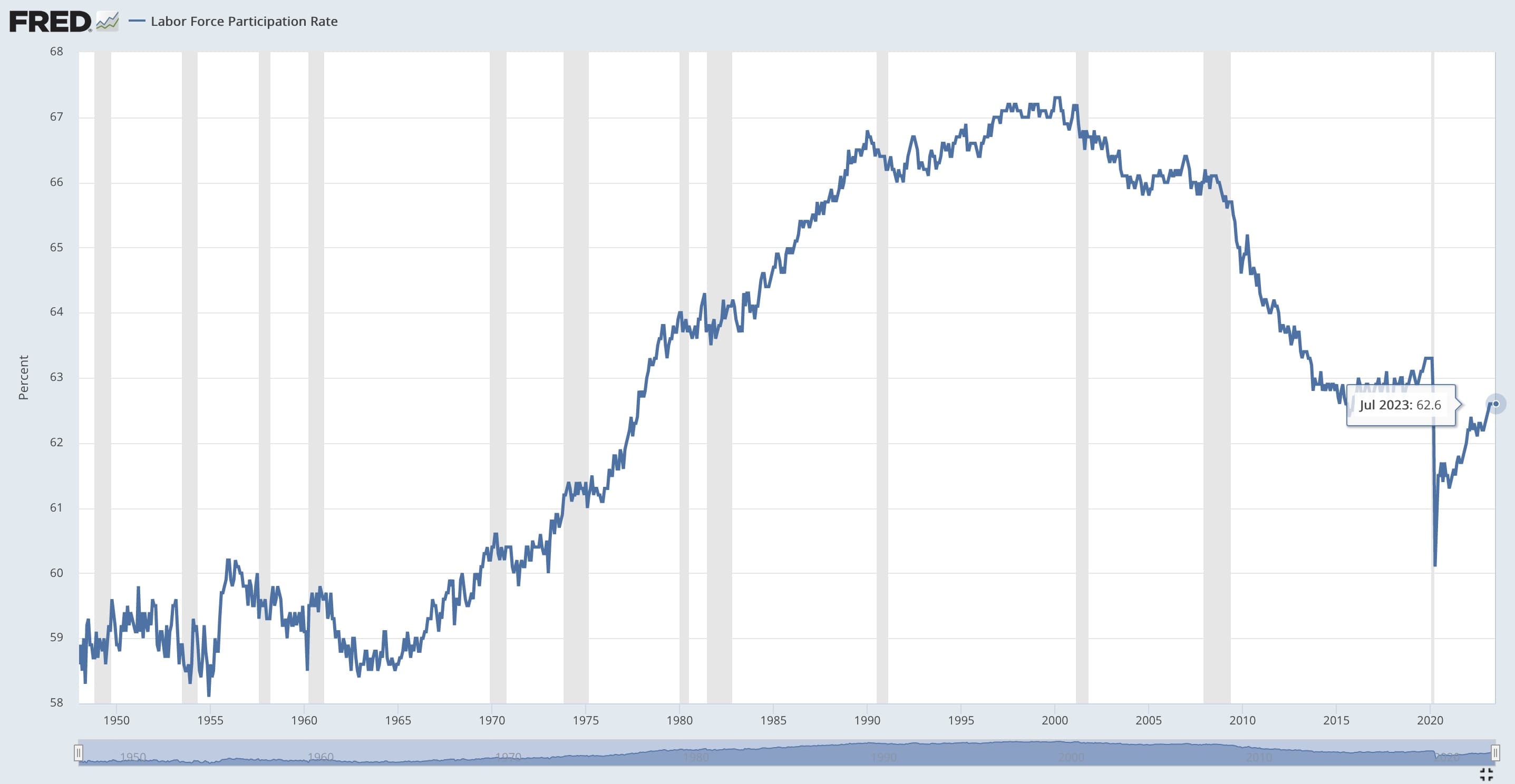

Yang warns there aren’t as many new jobs being created as there used to and eventually we’ll have a negative job growth rate. But the amount of new jobs being created is irrelevant without taking into consideration population. That’s why the unemployment rate exists, but the problem with the unemployment rate is it doesn’t take into account “people who drop out of the workforce for any reason, including disability or simply giving up trying to find a job… It also doesn’t take into account people who are underemployed - that is, if a college graduate takes a job as a barista or other role that doesn’t require a degree.”

There is such a thing to help account for this called the “U-6” Unemployment rate, which does looks healthy and is currently at its lowest rate since we began tracking this metric (1994). However, we can also look at the arguably better civilian labor force participation rate, which is a percentage of the number of people in the labor force (people employed/looking for employment) compared to the total civilian population (over 16, non-military, not confined to an institution). Most notably, this includes people who have given up looking for work.

The current labor force participation rate is 62.6%, a rate which we haven’t seen since 2015, and since then the late 1970s. It’s down 7% since its all time high of around 67.3% in 2000. To put this into perspective, a 100 basis point decrease in the rate represents around 2.5M people leaving the labor force. So a 7% decrease represents 17.5M people.

While I’m not sure what a healthy labor force participation rate is, I assume more people working who are of working age is better for the economy, but 63% is in line with other comparable countries according to The World Bank:

| Country | Labor force participation rate (2022) |

|---|---|

| USA | 63% |

| China | 67% |

| Denmark | 63% |

| France | 56% |

| Germany | 62% |

| India | 49% |

| Japan | 62% |

| Netherlands | 66% |

| South Korea | 64% |

| UK | 62% |

Yang’s point is “the numbers clearly show an economy that is having a harder time creating new jobs at previous levels.” While jobs are still growing, job growth rate is on the decline and at a slower rate than the growth of the working age population.

So why is this happening? Yang’s big hypothesis is that automation and AI are taking jobs from people and will continue to take them in the future.

“Companies can now prosper, grow, and mint record profits without hiring many people or increasing wages. Both job creation and wage growth have been weaker than the top-line economic growth would suggest since the 1970s.”

Andrew Yang

The largest tech companies of today compared to the largest companies of the “last generation” have far less employees, but with a higher market cap.

Although Yang compared Apple to IBM as an example of this, I think a more revealing example of the direct effect technology has on jobs and company value is Blockbuster compared to Netflix. Blockbuster at its peak in 2004 employed 84,300 people with a market cap of $8.1B after adjusting for inflation. Netflix, who killed Blockbuster through technological innovation, employs just 12,800 people with a market cap of $186.9B - 85% less employees and a 2,207% higher market cap. Companies of today, with the advancements in technology, can create much more valuable companies with much fewer employees.

Who is normal in America

We tend to derive our sense of the country by what we see around us, but the following statistics probably show an America very different from what you’re familiar with.

This is normal according to the U.S. Census Bureau:

- only 38% of Americans 25 years and older have a bachelor’s degree or more; 61% if Asian, 42% if white, 28% if black, and only 21% if Hispanic (2021)

- median personal income of Americans 25 years and older is $41.6k with nearly 70% making $65k or less (2021)

- 66% of Americans own their own home as of 2023, down from the high of 69% in 2005

In any case, the median income growth for people 25 years or older over the last 24 years (1997 to 2021) was only 14.9% after adjusting for inflation. The S&P 500, on the other hand, rose 190.9% over the same time period. This comparison isn’t made directly in The War on Normal People, but mediocre job and wage growth over the past 20 years shows that a rising stock market doesn’t drive or align with wage growth. It is likely more correlated with unemployment rates, but is it also correlated with wealth?

“We tend to use the stock market’s performance as a shorthand indicator of national well-being. However, the median level of stock market investment is close to zero. Only 52% of Americans own any stock through a stock mutual fund or a self-directed 401(k) or IRA, and the bottom 80% of Americans own only 8% of all stocks. […] This means that the average American benefits minimally from a rising stock market beyond the wealth effect, which is that the rich people around them spend more money and the economy is more buoyant.”

Andrew Yang

Although American stock ownership was at 52% in 2016, it is now at 61%, which has been about the average level. But according to the Federal Reserve, the bottom 90% of Americans by net worth do only own 11.1% of all stocks, which is a 37.9% decline since 1989. So an increasing stock market also adds only a little benefit to the wealth of most Americans.

What we do for a living

The five largest occupational groups in the US (in 2016) are office and administrative support, sales and retail, food preparation and serving, transportation and material moving, and production. In total, 69 million Americans work in these groups, which is 47% of the total American workforce. Yang claims each of these groups is at risk of being severely affected by automation and AI. As of 2021, production is no longer a top five occupation, and it has been replaced with management occupations. For the sake of covering the book, I’m going to ignore this change.

”Although the seriousness of [automation] has not reached the mainstream yet, […] many Americans are in danger of losing their job right now due to automation. Not in 10 or 15 years. Right now.”

Andrew Yang

Here is a table of the number of employees in these occupational groups from 2016 and 2021 compared to the total workforce.

| Occupational group | Total number of employees (2016) | Total number of employees (2021) | Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| All occupations | 140.4M | 158.1M | 13% |

| Office & admin. support | 22.0M | 19.6M | -11% |

| Sales & retail | 14.5M | 14.7M | -1% |

| Food prep. & serving | 13.0M | 11.8M | -9% |

| Transportation | 9.7M | 13.3M | 37% |

| Production | 9.1M | 8.8M | -3% |

In 2021, only one group did not decline in job count since 2016: transportation increased 37%. It’s difficult to say the decline in office and admin jobs was due mainly to automation without significant research. Transportation jobs jumped, but the decline of jobs in transportation is not expected until full autonomous trucks are ready for the market.

Yes it is interesting that four out of the top five occupations are declining, however total jobs are increasing and the occupations that are growing appear at first glance to have a higher median wage. Although this is good overall, this could be bad for the folks who are losing these jobs and don’t have the qualifications to enter the growing, and higher paying occupations.

About Transportation

Of all these occupational groups, Yang’s largest concern are truck drivers. At least in 2014, driving trucks is the most common job in 29 states with 3.54 million truck drivers nationwide (2022). They are mostly high school graduate men with an average age of 49.

There are huge financial incentives for transportation companies to adopt autonomous transportation vehicles. Not only are the 3.5 million truck drivers at risk of losing their jobs, but also the businesses along these routes to serve the drivers when they need to eat, drink, rest, sleep etc. Yang claims there are “as many as 7.2 million workers [who] serve the needs of divers at truck stops, diners, motels and other businesses,” but his source for this figure didn’t specify this number and the American Trucking Associations put the figure at 4.35 million, however it’s not clear if this figure also represents workers outside of the trucking industry who serve truckers.

In any case, as of 2021 and compared to 2016 and back to 2000, jobs in the transportation sector have greatly increased. However, autonomous trucks have yet to really hit the market so the impact of automation on this and related industries are yet to be seen and Yang can’t say “I told you so” just yet.

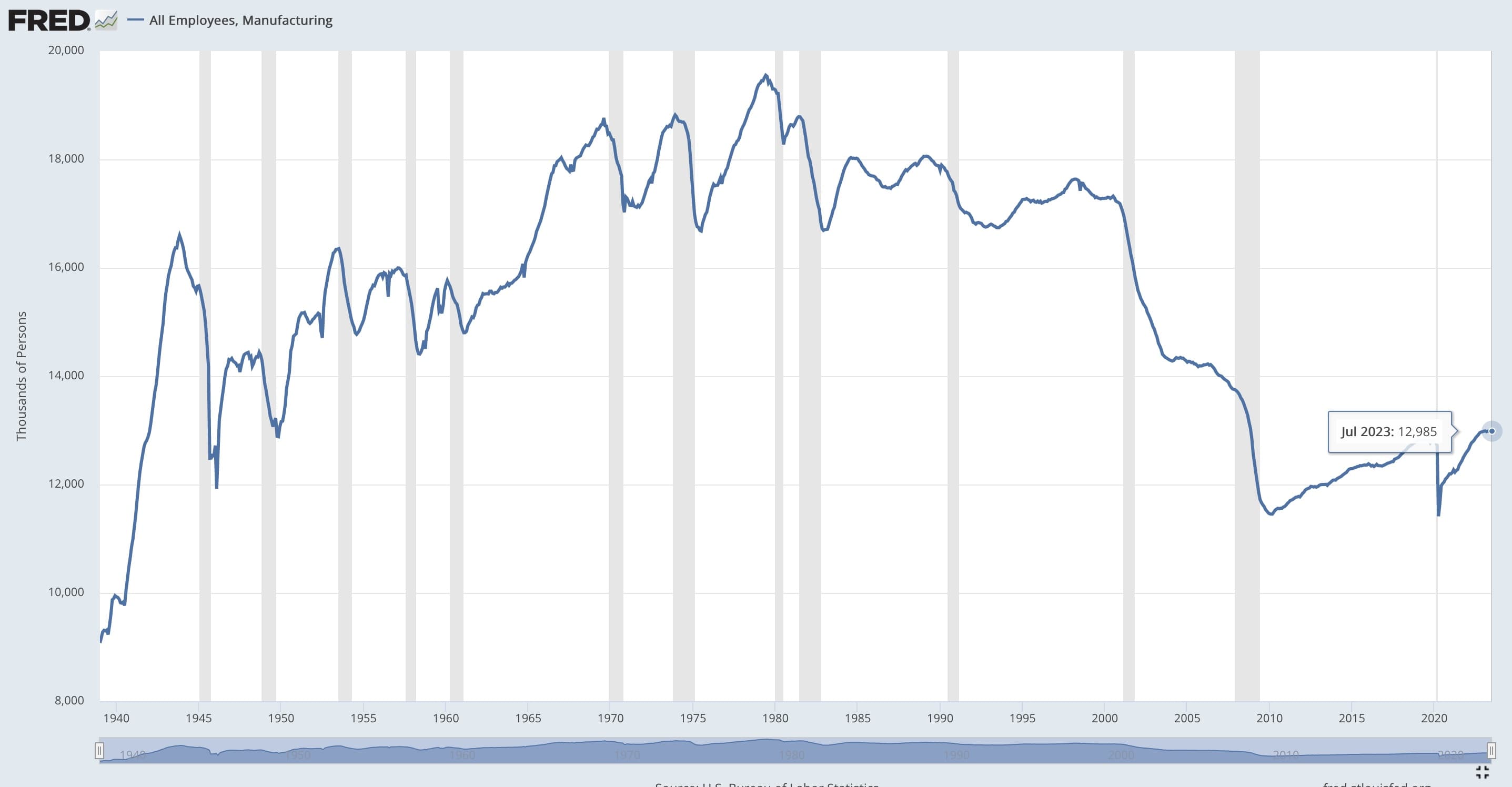

About Production

More than 5 million manufacturing workers lost their jobs after the year 2000, due to a combination of trade (outsourcing) and automation. Although there is debate as to which is the major cause, Yang cites a Ball State University study that attributes 85% of these job losses to technological change and automation.

A 2013 survey of these displaced manufacturing workers found that 41% were still unemployed by January 2012 or dropped out of the labor market within three years of losing their job. Of the 59% who found re-employment, 69% found employment in different fields. The manufacturing jobs that still exist are requiring more technical expertise and advanced education. Since 2000, manufacturing jobs for people with less than a high-school education fell 44% and jobs requiring a graduate degree grew by 32%.

Many of the 41% of displaced manufacturing workers become destitute and apply for disability to survive. From 2000 to 2011, the number of workers on disability rose by 3.5 million. Yang states this was mostly in manufacturing-heavy states like Ohio, Michigan and Pennsylvania, but he didn’t provide a specific source other than Michigan. About half of the 310,000 residents who left the workforce in Michigan between 2003 and 2013 went on disability. One in 12 adults aged 18-64 in Michigan receive disability and it’s the state with the 7th largest population receiving disability.

As of 2023, manufacturing jobs have not recovered to the levels seen in 2,000. The above data shows that it’s difficult for these people to find new work; however, and it bears repeating, the total number of employed people is still growing. The situation these folks find themselves is unfortunate, but whether this is a piece of a bigger crisis to come is unknown.

About White Collar Jobs and AI

Automation is not limited to replacing just blue-collar jobs with routine functions, but also white collar jobs including doctors, lawyers, accountants, wealth advisors, traders, psychologists, and more.

Super-intelligent computers (and AI), are entering the market, which can synthesize complex data sets, perform tasks, and make decisions as good as or better than humans, leading to a dramatic change in the way companies operate and employ people. As time goes on, “employing lots of people will mean that you’re behind the times.”

The Federal Reserve categorizes 44% of total jobs as routine, which are in danger of automation and AI to replace workers. As this occurs, workers will only be left with either low-end service jobs or high-end cognitive jobs with middle-skill jobs disappearing. The Fed is calling this “job polarization” and will lead to increasing income inequality.

On Humanity and Work

“It’s worth considering whether humans are not actually best suited for many forms of work. Consider also the reverse: Are most forms of work ideal for humans? That is, if we’re not good for work, is work good for us?”

Andrew Yang

The relationship between humanity and work reveals a negative correlation between the most human roles and their monetary compensation. While roles such as parent, artist, or teacher often have high social impact, they typically receive low or no pay. Conversely, lucrative jobs like corporate lawyers or financiers require a higher degree of efficiency and detachment from human qualities.

Part two: What’s happening to us

In part two, Yang makes several points about how the quality of life for normal Americans is breaking down in different ways.

Life in the bubble

Our smartest college graduates are being absorbed by the financial services and technology industries out of Manhattan and Silicon Valley. Why? They want to succeed and success is heavily defined by market success. And failure to succeed brings catastrophic economic and social consequences. So college isn’t a time for intellectual exploration, it’s a mass sift that determines one’s future prospects and lot in life.

“In the bubble, many of us came up through the meritocracy and we’ve internalized its lessons. The underlying logic of the meritocratic system is this: if you’re successful, it’s because you’re smart and hardworking, and thus virtuous. If you’re poor or unsuccessful, it’s because you’re lazy and/or stupid and of subpar character. The people at the top belong there and the people at the bottom only have themselves to blame.”

Andrew Yang

But success in entering these industries isn’t actually as meritocratic as the ones in the bubble like to admit. It’s more so based on one’s family background, the community in which one lives, and one’s ability to score high on tests. Therefore if success and a life worth living is defined by market success, then human worth is defined by test scores.

“The logic of the marketplace is seductive to all of us. It gives everything a tinge of justice. It makes the suffering of the marginalized more palatable, in that there’s a sense that they deserve it. Perhaps the most remarkable thing is that they often agree - they think they deserve it, too.”

Andrew Yang

Mindsets of Scarcity and Abundance

This is a mindset of scarcity. The average American lives paycheck to paycheck with a variable work schedule. This means they spend a lot of bandwidth stressing about uncertainties - enough hours to work, enough money to pay bills, what days they have off to set appointments, etc.

“A culture of scarcity is a culture of negativity. People think about what can go wrong. They attacked each other. Tribalism and divisiveness go way up. Reason starts to lose ground. Decision-making gets systematically worse. Acts of sustained optimism - getting married, starting a business, moving for a new job - all go down. If this seems familiar, this is exactly what we’re seeing by the numbers here in America. We are quickly transforming from the land of plenty to the land of “you get yours, I’ll get mine.”

Andrew Yang

Geography is Destiny

When the available good jobs and opportunity start decreasing in a city or town, the first people to leave are the most educated who have the best opportunities elsewhere. So they move out, and the average education level of that city starts to decrease as well. This is why America’s most educated people congregate in CA (Silicon Valley) and NY (Manhattan) and smaller cities tend not to prosper at the same rate. Although remote work is starting to change this, it is yet to be determined if this is a long term trend.

In the last 15 years, the majority of cities in America have seen more business close than open.

“A series of studies by the economists Raj Chetty and Nathaniel Hendren showed how important where you grow up is to your future prospects… If a child from a low-mobility area moved to a better-performing area, each year produced positive effects on his or her future earnings. They were also more likely to attend college, less likely to become single parents, and more likely to earn more with each year spent in the better environment.”

Andrew Yang

Men, Women, and Children

“A Pew research study showed that many men are foregoing or delaying marriage because they do not feel financially secure. The same study said that, for women, having a steady job was the single biggest factor they were looking for in a spouse. Getting married is an act of optimism, stability, and prosperity. It can also be expensive. If you don’t have a stable job all of the above becomes more difficult.”

Andrew Yang

Across all education attainment levels, marriage rates are declining, but are declining much more sharply in the lowest levels of education attinment.

The number of babies born to unmarried women is 40%, up from 30% in the early 1990’s, and up from 15% in the late 1970’s.

“At a time when raising and educating children and forming our human capital is of the utmost importance, we’re heading in the other direction.”

Andrew Yang

The Permanent Shadow Class: What Displacement Looks Like

There is an absurd amount of Americans on and applying for disability benefits every year. In 2014, nearly 2.5m Americans applied for disability and 9m working-age Americans are currently receiving disability benefits. It has become not only a bloated bureaucratic government program, but also a big private industry.

After someone receives disability benefits, only 1% ever return to the workforce despite the average monthly benefit amount being only $1,234/mo as of 2019. This is barely enough to keep someone above the poverty line.

“The fact that a program designed for a relatively small number of Americans has now become such a major lifeline for people and communities is part of the Great Displacement. […] After one gets on disability, one enters a permanent shadow class of beneficiaries. Even if you start feeling better, you’re not going to risk a lifetime of benefits for a tenuous job that could disappear at any moment. And it’s likely easier to think of yourself as genuinely disabled than as someone cheating society for a monthly draw.”

Andrew Yang

“Disability illustrates the challenges of mandating the government to administer such a large-scale program. It’s essentially the worst of all worlds, as the truly disabled and needy may find themselves shut out by red tape, while the process rewards those who lawyer up and the lawyers themselves. It sends a pervasive message of “game the system and get money” and “think of yourself as incompetent and incapable of work.” It’s subject to fraud. And once you’re on, you never leave.”

Andrew Yang

The Shape We’re In / Disintegration

These worrying trends show Americans are not in great shape right now and will make transitioning to a new economy much more difficult:

- we are getting older

- we don’t have adequate savings

- we are financially insecure

- we use a lot of drugs

- we are not starting new businesses

- we’re depressed

- we owe a lot of money, public and private

- our education system underperforms

- our economy is consolidating around a few mega-powerful firms in our most important industries

- our media is fragmented

- our social capital is lower

- we don’t trust institutions anymore

“Among the things being questioned is our capitalist system. Among young people, polls show a very high degree of sympathy for other types of economies, in part because they’ve witnessed capitalism’s failures and excesses these past years.”

Andrew Yang

“…capitalism, with the assistance of technology, is about to turn on normal people. Capital and efficiency will prefer robots, software, AI, and machines to people more and more. [Capitalism and technology] started saying things like, “Ah, let’s automate everything” and “if the market doesn’t like it, get rid of it,” which made reasonable people increasingly nervous.”

Andrew Yang

If capitalism in America continues as it is with the rise of AI and automation, there will be an even more staggering increase in income inequality. Society will be dramatically bifurcated between the rich (educated) and poor (uneducated), desperation and destabilization will rise, and could spur a revolution.

“If there is a revolution, it is likely to be born of race and identity with automation-driven economics as the underlying force. A highly disproportionate number of people at the top will be educated whites, Jews, and Asians… African Americans and Latinos will almost certainly make up a disproportionate number of the less privileged in the wake of automation, as they currently enjoy lower levels of wealth and education. Racial inequality will become all the more jarring as the new majority remains on the outside. […] Less privileged whites may be more likely to blame people of color, immigrants, or shifting cultural norms for their diminishing stature and shattered communities than they will automation and the capitalist system. Culture wars will be the proxy wars for the economic backdrop.”

Andrew Yang

Part Three: Solutions and Human Capitalism

The Freedom Dividend

The core solution Yang advocates for is a universal basic income - a monthly check of $1,000 to each U.S. citizen above the age of 18 regardless of the city they live in, the number of dependents they have, work status, or the amount of income they have.

“The first major change would be to implement a universal basic income (UBI), which I would call the ‘Freedom Dividend.’ The United States should provide an annual income of $12,000 for each American aged 18 [and above], with the amount indexed to increase with inflation. It would require a constitutional super majority to modify or amend. The Freedom Dividend would replace the vast majority of existing welfare programs. This plan was proposed by Andy Stern, the former head of the largest labor union in the country, in his book Raising the Floor. The poverty line is currently $11,770. We would essentially be bringing all Americans to the poverty line and alleviate gross poverty.”

Andrew Yang

There are three main critiques of UBI that make people quickly dismiss even considering it. These are:

- $1,000/mo is only enough money to scrape by

- it will cost too much to implement

- it will cause runaway inflation

But first let’s talk about why UBI is worth considering before addressing these critiques.

Benefits of UBI

In contrast to traditional welfare programs, a UBI with no strings attached removes the disincentive for people to work as wages earned from working will stack on top of UBI. And in contrast to increasing minimum wages, it will give people more flexibility with the work they choose.

- It would be a massive stimulus to lower-cost areas of living as the spending power of residents dramatically increases.

- It would make losing a job less stressful.

- It would empower workers with the ability to leave exploitative employers and find better work environments.

- It would allow people to work jobs they enjoy even if the pay is less than they could earn in a job they dislike.

- It would help people avoid making terrible decisions based on financial scarcity and month-to-month needs.

- It would increase rates of entrepreneurship by reducing the risk of starting a business.

- It would enable people to more effectively transition from shrinking industries and environments to new ones.

- It would reduce stress, improve health, decrease crime, and strengthen relationships.

- It would support parents and caretakers for the work that they do, particularly mothers.

- It would give all citizens an honest stake in society and a sense of the future.

- It would stimulate and maintain the consumer economy through the automation wave.

- It would maintain order and preserve our way of life through the greatest economic and social transition in history.

- It would make our society more equitable, fair, and just.

Cost

To give $1,000/mo to all citizens above the age of 18 would cost somewhere around $1.3 trillion per year. So how could the US government pay for it? The two biggest sources of potential are folding existing welfare programs and implementing a new value added tax (VAT). A VAT is a tax on consumption, levied on non-essential goods.

All developed countries have a VAT except for the US. And in Europe, the average VAT is 20%. A VAT’s efficacy has been solidly established. Obviously, implementing a VAT on non-essential goods would increase the cost of those goods; however, essential goods for people’s basic needs shouldn’t be affected. This means people with a low income who spend the majority of their income on essential goods will be affected the least from a VAT and will benefit the most from UBI. At a 20% VAT, one spending less than $60,000 per year on non-essential goods will come out on top with a UBI + VAT policy (20% of $60k = $12k). Therefore, only high income earners (and spenders) will pay more in tax after their UBI is accounted for.

Also, not every category of good would have a 20% VAT. Depending on the type of good, a different percentage of a VAT could be applied. For example, clothing could have a 10% VAT while new cars could have a 25% VAT and et cetera. These percentages could be tweaked to again affect low income earners and spenders less so than high income earners and spenders.

“UBI… is not shaming - everyone participates. It does not try to control the economy from the top - people can spend their money on what they want and therefore steer the economy as it has always been best steered, by the consumer. It could free up the job market in ways that are hard to appreciate… I am entranced by UBI, not just as a needed fix but as an institute that unleashes people’s potential… I find myself convinced that UBI is natural, and would lead to a more productive and happier world - and it would allow us to fully harness people’s creativity and the technology they create.”

Richard Garfield, creator of Magic: The Gathering

Unlike America’s current welfare program, a UBI shouldn’t increase the size of the government or create a new bureaucracy. There would be no qualifying criteria or capacity limits and therefore no need for the thousands of government employees that are needed to administer today’s welfare benefits.

“[UBI is] less an expenditure and more a transfer to citizens so they can use it to improve their lives, pay each other, patron the local businesses, and support the consumer economy. Instead of hiring a new army of government employees, every dollar will be put into the hands of an American citizen and then largely spent within the American economy.

Andrew Yang

Some critics of UBI might say that if we give people cash instead of vouchers (like food stamps), people will just spend it on drugs, alcohol, or gamble it away.

“The idea that poor people will be irresponsible with their money and squander it seems to be a product of deep-seated biases rather than emblematic of the truth. There’s a tendency for rich people to dismiss poor people as weak-willed children with no cost discipline. The evidence runs in the other direction. As the Dutch philosopher Rutger Bregman and others put it, “Poverty is not a lack of character. It’s a lack of cash.” “Scarcity research indicates that the best way to improve decision making is to free up people’s bandwidth. People won’t ever make perfect choices. But knowing that their basic needs are accounted for will lead to better choices for millions of people each day.”

Andrew Yang

In contrast to a job guarantee policy, which would be very difficult to organize and create a huge bureaucracy, a UBI would more naturally create jobs.

“Many people have some artistic passion that they would pursue if they didn’t need to worry about feeding themselves next month. A UBI would be perhaps the greatest catalyst to human creativity we have ever seen. Perhaps most crucially, endless new businesses would form. This would play out over and over again throughout the economy, resulting in millions of new jobs - 4.7 million according to the Roosevelt Institute’s analysis. A UBI would address a significant proportion of the lack of work through increased humanity, caring, creativity, and enterprise.”

Andrew Yang

Human Capitalism

What is the goal of our country? Of our government? Well, outside of wartime, the answer seems absent other than increasing GDP every year and keeping inflation and unemployment in control - all economy focused. But should it not be to ever improve the lives of all its citizens?

In part one of the book, it’s clear improving the well-being of citizens is not the goal. If it is, then we’re doing the exact opposite. Instead of improving the economy above all else, Yang proposes what he calls “Human Capitalism,” which is geared toward maximizing human well-being and fulfillment.

“Human Capitalism would have a few core tenets: (1.) Humanity is more important than money. (2.) The unit of an economy is each person, each dollar. (3.) Markets exist to serve our common goals and values.”

Andrew Yang

“Our economic system must shift to focus on bettering the lot of the average person. Capitalism has to be made to serve human ends and goals, rather than have our humanity subverted to serve the marketplace. We shape the system. We own it, not the other way around.”

Andrew Yang

So, how do we measure a country’s current state and progress of improving the well-being and fulfillment of its citizens? Here are some ideas Yang proposes:

- median income and standard of living

- levels of engagement with work and labor participation rate

- health-adjusted life expectancy

- childhood success rates

- infant mortality

- surveys of national well-being

- average physical fitness and mental health

- quality of infrastructure

- proportion of elderly in quality care

- human capital development and access to education

- marriage rates and success

- deaths of despair/despair index/substance abuse

- national optimism/mindset of abundance

- community integrity and social capital

- environmental quality

- reacclimation of incarcerated individuals and rates of criminality

“Human Capitalism will reshape the way we measure value and progress, and help us redefine why we do what we do.”

Andrew Yang

Yang continues this section of the book on requirements for human capitalism to take effect in our government with ideas and suggestions for new policies to help the US get closer. Ideas range from congressional salary changes, work restrictions after terms are over, anti-corruption/anti-lobbying, and more.

Additionally, Yang has various ideas to improve the health care system because how it’s setup currently doesn’t provide the best incentives for either businesses, care providers, or the people receiving care.

In regards to improving the lives of people at the individual level, Yang focuses heavily on education, suggesting improvements in both quality and access. As shown in part one, a person’s education level is one of the biggest leading indicators of one’s earning potential and quality of life. Yang dissects many of the issues with the current education system in the US and provides ideas and suggestions on how to address them.

I’ve reduced a great length of the end of the book into the previous three paragraphs. While each chapter I’ve found very interesting, I think the core ideas of UBI and human-centered capitalism to be the most important in his book.

What I love most about Yang’s “The War on Normal People” is its theory on how a country ought to be, what it should strive for, and how its progress toward that goal ought to be measured. I recommend this book for people interested in data-driven political theory and political ideas outside contemporary thought.

You might also enjoy

-

Untethered Soul by Michael Singer—Summary, Notes, + Quotes

A spiritual exploration into who we are and who we ought to be.

-

I Will Teach You to Be Rich—Summary, Notes, + Quotes

The best introduction to personal finance and how to enjoy spending your money.

-

The Effective Executive—Summary, Notes, + Quotes

The essential handbook to learn leadership and effectiveness at work.

-

Mastery by Robert Greene—Summary, Notes, + Quotes

The essential book to help you find your purpose.

Never Miss an Article

Get notified by email when I publish a new article.